The New Yorker has a very interesting essay up on the work of the artist Oh U-Am, whose oeuvre focuses upon the rapid transition — in the space of a single extended generation — of his native Korea from war-ruined privation to extraordinarily advanced material prosperity. (Korea coverage in general, and not just in The New Yorker, seems to have improved lately — I’m not quite sure why — so check out also the E. Tammy Kim piece on US-ROK wargames in the same publication.) The piece is well worth your time, not least because Oh’s life and background are extraordinary. One pull suffices:

“I remember kids throwing rocks at the North Korea People’s Army and climbing up on tanks,” [Oh] explained. During the Korean War, Oh’s mother had been kidnapped and killed for serving food to soldiers on the wrong side of the civil conflict. “When I became an orphan, I suffered a great trauma,” he said, motioning to his stomach. He and his two brothers shuffled from place to place, and he managed to attend only elementary school. After the war, he enlisted in the South Korean Marine Corps (“I went because I was getting beat up. I wanted to be feared”), then found work as a resident handyman in a nunnery near Busan. For the next three decades, he drove the nuns around town and maintained the heating system and the garden. “In the boiler room”—where there was surplus enamel paint and wood boards—“sometimes I didn’t have a lot to do, so I began to paint,” he told me.

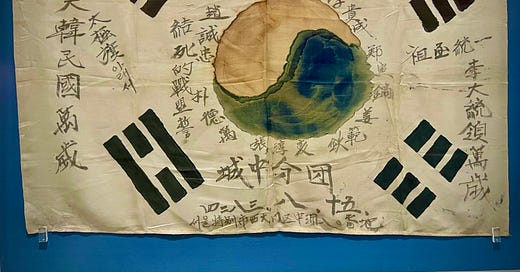

The artist’s tale reminded me of the 2004 Korean film — released long before Korean cinema could bank on a shot at an American audience, and therefore not well known — Taegukgi: The Brotherhood of War, which focuses upon the based-on-thousands-of-true-stories tale of two brothers in the Korean War. Inevitably, one of them fights for the Communists, and the other for the republic — and just as inevitably, the culminating scene has them meet on the battlefield. I’m not giving anything away with the revelation: good cinema is characterized by excellent process, in my view, rather than outcomes, and Taegukgi is a good in exactly this vein. The scene where the Southern brother’s unit, enraged by a Communist massacre of villagers, goes on a revenge hunt will suffice to illustrate the whole.

The Korean War in general doesn’t get the American attention it deserves, in either popular memory or scholarship. Taegukgi rectifies that to an extent, in communicating the intra-communal savagery of it, and — in its bookended opening and closing, which I will not spoil here — in showing the profound disconnect from that era and ours. The war was massive in ways Americans don’t quite grasp. The United States lost about thirty-six thousand in battle in that war, expanded to about fifty-four thousand altogether. The Koreans, on the other hand, lost about three million — a literal decimation of North and South alike, in a total peninsular population (in 1950) of just over thirty million. One in ten of everyone dead: it’s nearly impossible to imagine anything like it, including for a modern, post-democratic-opening Korean.

I wrote that “Oh’s life and background are extraordinary,” and indeed they are, but they are also exceptionally common for a Korean of his generation. The nation was built, raised up from literal wreckage, by a generation that endured truly rending levels of suffering. When we lived in Seoul in the early 1980s, the most-popular show on KBS was called Finding Dispersed Families, which worked to reunite loved ones separated by a war that was then only thirty years distant. The format of the show would, I suppose, be called reality television now, but that connotes a cheap and confected quality that simply isn’t present here. If you wanted to appear on Finding Dispersed Families, you got in touch with your local KBS affiliate, told them about the loved ones the war took from you, and it would work with the other KBS affiliates to track them down. Have a watch —

KBS has done a great job putting these archives on the Internet. There are a ton of them — the program ended up reuniting over ten thousand families, a tremendous number and also a drop in the ocean of Korean wartime suffering and separation — but watch this one for an example that is indicative of the rest. Turn your captions on unless you speak 한국어를 —

It would take a heart of stone to remain unmoved, or membership in the Workers' Party of Korea.

The American literature on the war is slowly improving, as it is on Korean history in general — which is in no small part a byproduct of Korea’s burgeoning cultural power. It is even possible now to get some decent English-language books, though by no means enough, on the Great East Asian War of 1592-1598. If you’re like nearly everyone in the West, you’ve never heard of this absolutely stupendous conflict involving Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Japan, Ming-dynasty China, Joseon Korea, and even (very peripherally) a handful of European powers. It was even an episode of Catholic expansion in east Asia, as several of the major Japanese lords involved were Catholic, and their invasions introduced Catholicism to Korea — at the sword, to be sure — for the first time. The stupefying size of the war is best communicated by a single comparative fact: the Japanese cross-strait invasion force would not be matched in size anywhere in the word for another three and a half centuries, until Operation Overlord in 1944.

There’s a solid Korean war movie about this too, a trilogy in fact: 2014’s The Admiral, 2022’s Hansan, and the forthcoming Noryang. All three center upon the intrepid Korean Admiral Yi Sun-sin, who won the war for the Joseon-Ming alliance by understanding that the Japanese, fortified with European firearms and methods, could not be beaten on land — but their supply and communications could be severed by sea. The Hansan trailer does it justice:

There’s a reason the main thoroughfare in Seoul, the Sejong-daero leading to the Gyeongbokgung Palace and in line to the presidential residence at the Blue House, features statues of only two men. One is King Sejong the Great, who invented hangul, the Korean script, in the fifteenth century. The other is Admiral Yi.

As for the American literature on the (modern) Korean War, the standard remains T.R. Fehrenbach’s 1963 This Kind of War, which — though suffering from Fehrenbach’s typical dismissal of annotated sourcing — remains the only one to give the reader a sense of the strategic course of the war following spring 1951. That moment is where most histories stop, except to note a stalemate and tortuous negotiations, but Fehrenbach explains the rationale behind events, and his work is recommended. All this said, Allan Millet at the University of New Orleans is presently writing the third volume of his own Korean-War trilogy that will, I suspect, become the standard work and eclipse Fehrenbach entirely. In The War for Korea, 1945-1950: A House Burning, Millet makes an absolutely convincing case that the Korean War actually began in the late 1940s, as an insurgency-centric effort that the Republic soundly defeated. The North-Korean conventional invasion of June 1950 in this telling is a response to that outcome: it was the only option left for reunification on Communist terms. I learned more about the birth of modern Korean nationhood from Millet’s single volume here than I did from any other source — and he persuasively shows how the South developed a political and civic culture cohesive enough to endure the shock of invasion and near-defeat. The second volume, The War for Korea, 1950-1951: They Came from the North, remains on my shelf still unread — a fate shared by many companion tomes — but the consensus from its reviews is that it is comparably insightful.

So then, from all that …

… to all this.

The lifetime of Oh U-Am encompasses it all. It has not been a clean progression. Again, from the New Yorker essay:

In the space of a few decades, Oh and his grown children had come to live relatively well, and South Korea had become a wealthy nation. The flip side was a certain alienation: people seemed untethered from one another and their messy, bloody collective past.

Chang Kyung-sup, a Professor of Sociology at Seoul National University, has popularized the term compressed modernity to describe that “certain alienation,” the social and psychic dislocation resulting from this sort of extremely rapid change:

Compressed modernity is a civilizational condition in which economic, political, social and/or cultural changes occur in an extremely condensed manner in respect to both time and space, and in which the dynamic coexistence of mutually disparate historical and social elements leads to the construction and reconstruction of a highly complex and fluid social system.

The Korea Society will have a webcast on it, featuring the professor, on February 9th. Compressed modernity reads to me very much like the thesis of Alvin Toffler’s 1970 Future Shock, also positing a dislocation from the rapidity of change, and Azeem Azhar’s Exponential View aspires to cover much of the same ground. Chang would probably disagree to some extent, in that he writes on the Korean case having unique features absent elsewhere:

Asian societies have been propelled into modernity too, but theirs is a compressed modernity, which displays very different traits … [compressed modernity in Korea] created a society that is haunted by various developmental and civilizational costs, such as endemic generational conflicts, overloaded family responsibilities and exceptionally high suicide rates.

I don’t dismiss his case, but I would need to see more to persuade me that this is something qualitatively different from the experience of rapid industrialization, urbanization, and wealth generation nearly everywhere else it has happened. The Korean experience in building an economy and a society of wealth is extraordinary indeed — and admirable. But other nations and peoples have done the same. What is unique about Korea is not the vertiginous experience of change.

It is its roots in war.