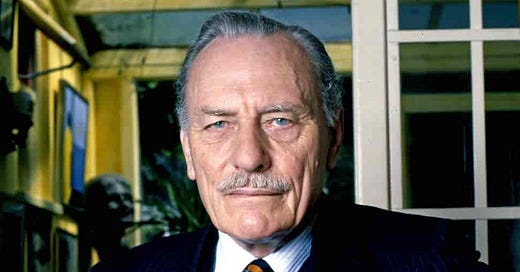

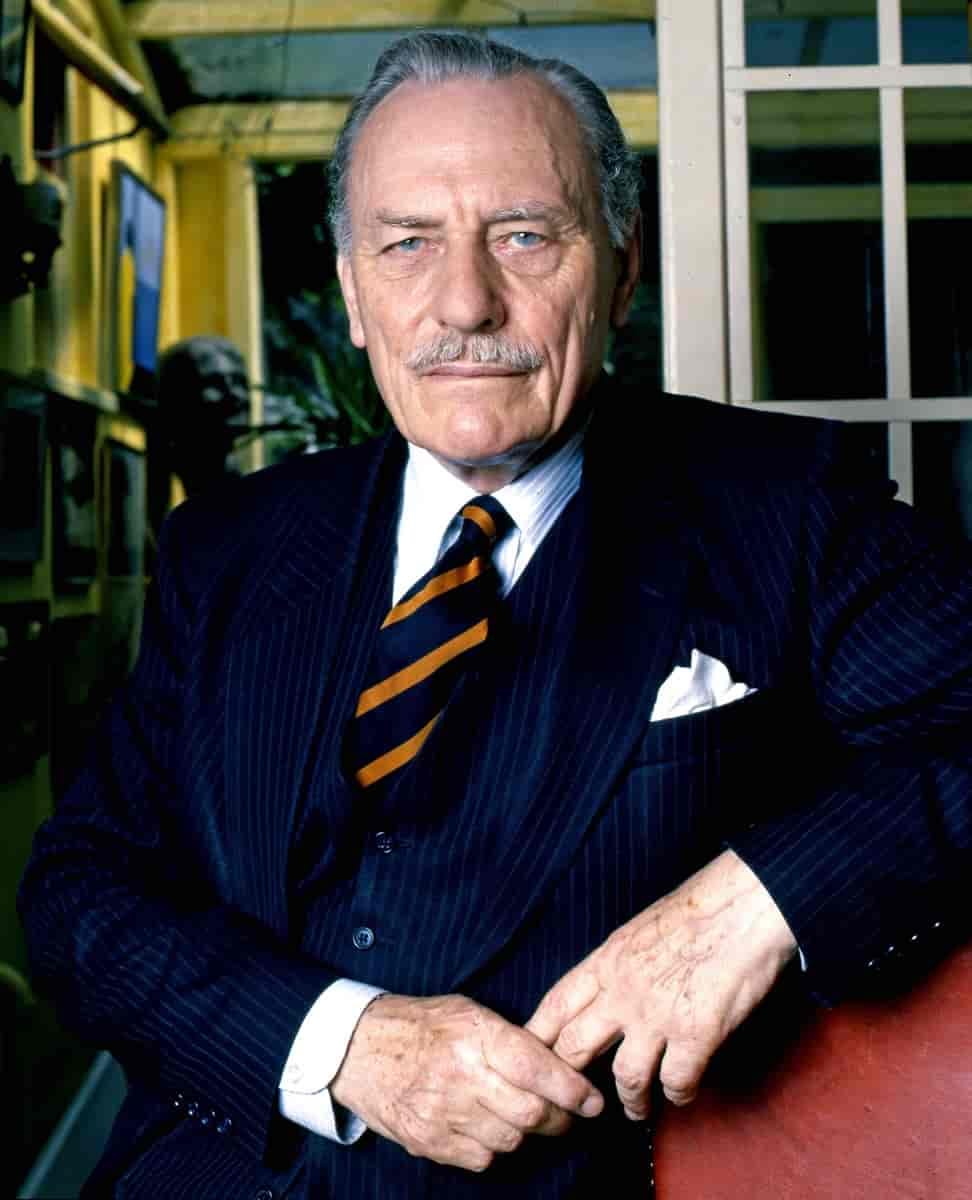

The British essayist John Casey penned a piece in The Spectator seventeen years ago, on the revival of the Conservative Philosophy Group that he co-founded in 1974. The commentary, a retrospective on the group’s original incarnation, included a remarkable recollection of ideological sparring between then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Enoch Powell, MP. This episode happened in 1982, shortly before the outbreak of the Falklands War. Casey tells it:

Mrs Thatcher came [to the Conservative Philosophy Group] only twice, once as prime minister. That was the occasion for a notable non-meeting of minds. Edward Norman (then Dean of Peterhouse) had attempted to mount a Christian argument for nuclear weapons. The discussion moved on to ‘Western values’. Mrs Thatcher said (in effect) that Norman had shown that the Bomb was necessary for the defence of our values. Powell: ‘No, we do not fight for values. I would fight for this country even if it had a communist government.’ Thatcher (it was just before the Argentinian invasion of the Falklands): ‘Nonsense, Enoch. If I send British troops abroad, it will be to defend our values.’ ‘No, Prime Minister, values exist in a transcendental realm, beyond space and time. They can neither be fought for, nor destroyed.’ Mrs Thatcher looked utterly baffled. She had just been presented with the difference between Toryism and American Republicanism.

Camilla Schofield’s 2013 book on Enoch Powell and the Making of Postcolonial Britain closes with Casey’s anecdote. Schofield observes, in the book’s final passage:

This disagreement, on the eve of the Falklands War, suggests Powell’s refusal to become a genuine member of Britain’s Thatcherite revolution. Thatcherism did not seek to conserve Powell’s ‘fragile web of understood relationships’ – the ‘little platoons’ of affection – that make up the conservative nation. There was no alternative; traditional industrial communities and the mediation of local governance could not survive. As one analysis put it: ‘Thatcherism enjoyed negative success as the corrosive agent which broke down the certainties of old forms of social life.’ If we look to Thatcher’s record, we see less a concern with the protection of particular institutions between the state and the individual, and more a sense that certain cultural and social forms enable a healthy market order. In this sense, in the long intellectual battle between Powell and what he regarded as an ‘American’ vision of the world, Powell lost.

It should be noted that this isn’t a universal view: here’s Robbie Shilliam in Tribune magazine, for example, arguing that Enoch Powell set forth the conditions from which Thatcherism emerged. There may be something to this, but I tend toward Schofield’s view of what Casey’s anecdote illuminates: that there was a fundamental difference between his understanding of conservatism, and Margaret Thatcher’s. I further concur that his vision succumbed to hers — it is nearly inarguable — and that further (this is my view, not Schofield’s) that the subsuming of what Casey calls “Toryism” is at the root of Britain’s troubles now, and ours too.

Thatcher is of course a revered figure on the right, at least in the United States, where the invocation of a sort of 1980s political trinity — President Reagan, Prime Minister Thatcher, and Pope John Paul II — is held to have saved civilization (explicitly) by winning the Cold War and (implicitly) by putting an end to the 1960s-1970s period of Western decline. It’s an understandable shorthand although it frays when pulled upon: the list of indispensable leaders also includes Mikhail Gorbachev and George H.W. Bush, for one thing, and it’s unlikely the contemporaneous Pope would have wanted to be remembered as part of a political project. (He was a great man of the West to be sure, and also not a free-market ideologist.) American critique of her from the right is therefore uncommon.

But critique there must be, because the market-mechanism primacy that overtook Anglosphere-conservative thought in that era, and continued unhindered until the fraught decade of the 2010s, has been a major factor in institutional conservatism’s failure to conserve — especially ways of life and societal ties within community that are properly the first objects of government. Thatcher on this point is frequently condemned for her infamous 1987 declaration that society does not exist, which is self-evidently untrue, although upon examination it seems she was merely phrasing inartfully, making a programmatic pronouncement rather than a considered ideological one. Nevertheless this has not stopped market ideologues from expounding upon the phrase and taking it to ends that are at first glance extraordinary. As an illustrative example, here’s G.R. Steele from 2009:

Any practical consideration of the broadest interests of “society” vanished with the emergence of a world economy structured upon the division of labour, free access to markets and individual choices. Our atavistic dispositions to the morality of the tribe, where individuals are bound by personal relationships, could never have supported the extended socio-economic order that has brought unsurpassed material benefits.

I write that this is “at first glance extraordinary,” because it is in its implications. What the passage here proposes is simply the theme, to which we’ve returned again and again, of the dissolution of the nation, the end of the partnership toward virtuous ends that is the fundamental quality of the Aristotelian state. Though the libertarians of various stripes likely don’t grasp it in these terms, the severance from the “tribe” and its interests, and the negation of “personal relationships,” is throwing the people into the pre-political state. “[U]nsurpassed material benefits” come with a fairly significant side effect in this framework: in material freedom we find the necessity of political rule. (I do not wish to characterize the whole thought and work of Steele, who I do not know: this passage is merely exemplary.)

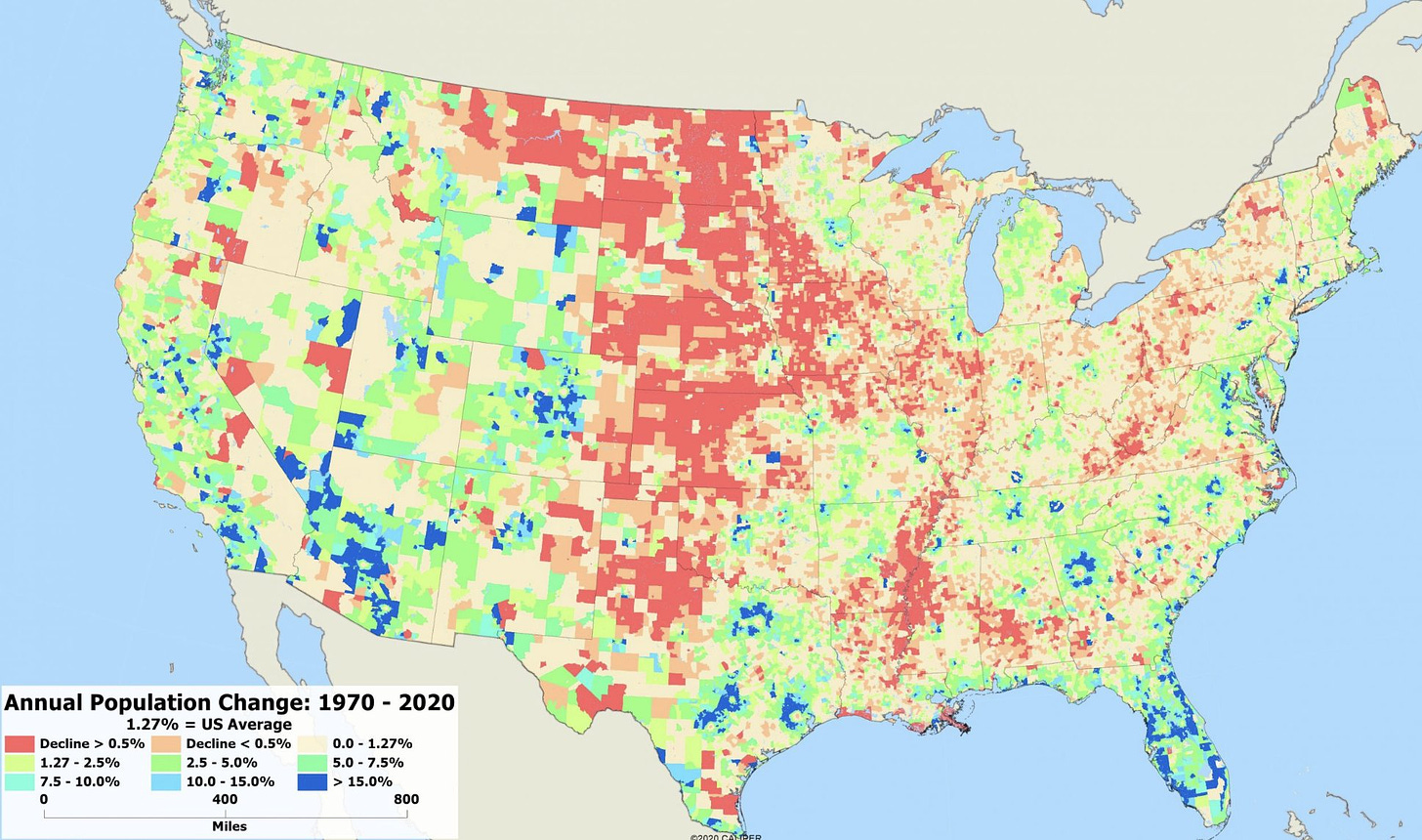

It is also not at all extraordinary in that this has been the actual basis of policy for generations now. In the American context, the whole ideology and program of trade for the past two generations has assumed two major things: first, that trade confers political change upon the trading nation, tending toward the benefit of the United States; and second, that the net benefit to the nation in efficiencies and prices exceeds the net loss in removal of productive capacity. The first item may be conclusively dismissed by the examples of China and Mexico, both regimes of which have moved toward ever-greater antagonism versus the United States in the decades since the opening of more-or-less free trade. The second item is a wholesale dismissal of the Hamiltonian concept — an example of American conservatism rejecting the Founders’ strategic insights — whose fruits are visible in this map of county-level population change in the U.S. across half a century since 1970:

What we see here are to a tremendous extent the outcomes of market-ideology supremacy. Agriculture, thrown increasingly toward globalized economies of scale, sees the consolidation and even elimination of communities west of the 100th meridian — and also east of it, in some of the continent’s richest lands in the once-glaciated plains of Iowa, Minnesota, and Illinois. The communities along the Mississippi River, once a massive artery of trade and transport, simply vanish. (As an experiment, which I have done, spend some time counting riverine traffic on the Mississippi, at, say, St Louis. Then do the same experiment on the Huangpu in Shanghai.) Most distressing, the communities alongside the Great Lakes — which on world-historical and geographical levels are positioned to be the most-prosperous and most-populated places of settlement anywhere — are in conditions of alternating stagnation and decline. Much of this is due to governance, yes — leftist governance has an extraordinary track record of impoverishing the most promising regions — but much of it is also due to regime decisions made in days past. For years, it was considered wise and farseeing to sign the death warrant of manufacturing in the Ohio River valley, so that manufacturing in Nuevo León and Shenzhen could flourish.

This calculus is many things, but it is not the proper course of a regime that acts for the nation. To the extent that Schofield’s description of “Powell’s ‘fragile web of understood relationships’ – the ‘little platoons’ of affection – that make up the conservative nation” characterizes his thought and preference, Enoch Powell was right.

There is one other thing he was right about: his declaration, in Casey’s telling, that he “would fight for this country even if it had a communist government.” This is met, according to Casey, by bafflement on Thatcher’s part. He writes that she was a subscriber to “American Republicanism,” but here he missteps, because what is really on display is American *propositionalism* — the concept of the nation as idea rather than people and place. Propositionalism has as one of its putative strengths its infinite extensibility: adhere to the proposition, and anyone can join the nation. Aristotle would recognize this as only partially constituting the nation: the partnership toward virtuous ends is in existence, but the philia required for the existence of the partnership (to say nothing of agreement upon the ends) is by no means assured. Powell highlights the corresponding weakness of propositionalism, in that it renders the allegiance to the nation conditional. The old formulation of “me against my brother, my brother and me against the world” is simplistic and primitive, but it is both those things because it is foundational. Without that foundation, you get what you see, for example, in Rod Dreher’s essay here, in which he notes that the propositional nation may find itself undefended.

It is undefended, if it is, because its ends have become unagreed and unvirtuous — and the propositional nation cannot survive that without reverting to the pre-political mechanism of plain repression. (We see this in the U.K. now, and also to varying degrees in the United States and Canada.) But the nation as defined by Aristotle, and as understood by Powell, can. To “fight for this country even if it had a communist government” is not an abdication of principle but an adherence to it — one that surpasses the pretenses of propositionalism in speaking to the real ties of community and obligation that create family, community, and state. Wrongly understood, it can elevate an evil regime as an end in itself, above the surpassing elements that create and constitute it: this is Völkisch ideology, a perversion. Properly understood, it is both Robert E. Lee concluding with regret that he must serve Virginia — and it is also the Russian Orthodox faithful defending their homes and existence by service in the Red Army — and it is also Blessd Franz Jägerstätter concluding that his obligations to religion, family, and community (the local, the personal, the interior) supersede those to the Third Reich. Pause here for a moment if you haven’t seen the 2019 Malick film on the last: it is heartbreaking and sublime, and that’s just the trailer.

All this requires something absent from the aesthetic of Thatcher and nearly the whole of American life and civics: a sense of tragedy. Within the array of cultures and folkways that constitute the United States, only the South possesses anything like that to any meaningful degree. (Honorable mention should go to Willa Cather’s Great Plains.) Tragedy, at the intersection of duty and desire, each pulling in opposite directions, is the prerequisite for Powell’s sense of patriotism. It is fundamental to the human condition — and the propositional nation, locked into a narrative of progress, does not have it, which is why it shudders into crisis when the narrative breaks.

Solzhenitsyn, in his epic August 1914, provides a Russian exposition of the quality:

She could not check herself and asked with shrill insistence, 'Where are you going? And why? ... You don't mean you're volunteering [for the war]?’ ...

She gripped his shoulders. 'Sanya! Don't go! Don't go away!' ... Sanya simply nodded. He had no arguments to use against her and did not try to defend himself. Sadly he said, 'I feel sorry for Russia.'

'Sorry for what? Sorry for Russia?' Varya jumped as if she had been stung. 'When you say Russia do you mean the idiot Emperor? The Black Hundred grocers? The long-skirted priests?'

Sanya did not answer. He could think of nothing to say. He just listened. But he did not lose his temper under the lash of her reproaches. Any argument was a chance for him to test himself.

'Anyway, who says you have the strength of character to be a soldier?' Varya was seizing any weapon that came to hand... 'And what about Tolstoy?' She had found the final argument. 'Have you asked yourself what Lev Tolstoy would say? Where are your principles? Where is your consistency?'

The light blue eyes under the corn-colored brows and above the corn-colored mustache were sad and unsure of themselves.

He raised his shoulders slightly and said barely audibly, 'I feel sorry for Russia.'

The conditional allegiance of propositionalism is easy by comparison. But this is the real thing, and it sustains nations unto the ages. If one believes in the regime, then the regime will fall, or worse, turn upon you. But if one believes in the nation — British, American, Texan, or any other — then this is something that may live. Not by markets, but by meaning, and by the people who bear it.