There are only two essential board games in my view. One is Go, or Weiqi if you prefer, the millennia-old abstract-strategy and positional-tactics board game that has been unsurpassed in complexity and subtlety since its emergence in Zhou-dynasty China. I first encountered Go in Korea nearly forty years ago, but it was another two decades before I could credibly play it. Even now, I struggle with it: my seven-year old son is already competent to consistently thwart me, if not defeat me, in our matches. Yet it rewards the effort. Go compels me to think positionally and over the long term, while retaining an awareness that minor detail — the placement of a single stone — is often the difference between victory and defeat. Draw your life metaphors as you will. Some things ought to be pursued not because one is good at it, but because one is not.

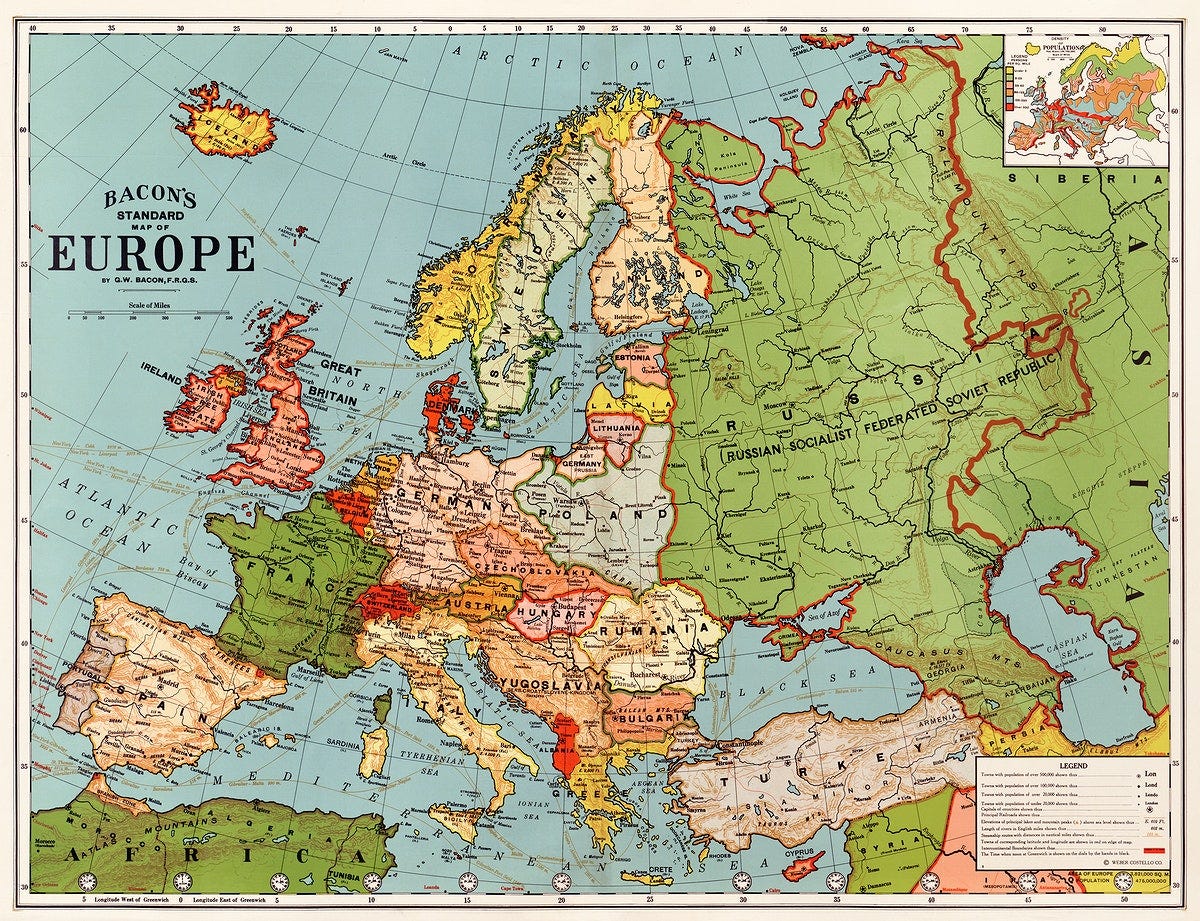

The other essential board game is much more recent, and much more topically immediate. Allan Calhamer’s 1954 Diplomacy is also a game of positional strategy among equal playing elements — with significant topological modifications to Go’s uniform grid, being a rough map of Europe c.1901 — and with the addition of a crucial element that Go largely lacks. Diplomacy requires, well, diplomacy: players must negotiate with one another to survive and win. If Go is essential because of its structural and logical elements, then Diplomacy is the addition of the humanities to that mix. It is a game, above all else, of the human element.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Armas to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.