The synthesis of right and right.

Understanding the future of conservatism through Boydian theory.

Some days back I saw a comment on one of the too-numerous content channels on the Internet, to the effect that though the populist right is making all the noise, it’s the institutionalist right that’s racking up all the wins. The context was the profusion of Supreme Court victories — chief among them the end of Chevron deference — that have mostly been the outcome of years of careful litigation by what gets derided in some corners as Conservatism Inc. (The SCOTUS affirmation of presidential prerogative and immunities is much less plausibly an outcome of that cohort, and anyway will abruptly become considerably less revolutionary and downright conservative in the media eye once it is seen to protect a Democratic president.) The observation isn’t new: in the Dobbs decision two years back that overturned Roe, there were similar comments to the effect that Conservatism Inc. was in fact fairly effective, or at least more effective than its rightward critics. At the time, I observed much the same.

Upon reflection, I think this was wrong — and not because either cohort has a superior case versus the other. They do each, however, have superior cases for themselves. Conservatism Inc. (however we are defining it) is not useless; and the populist right (or the National Conservatives, depending) is not simply a force of destruction. It seems inarguable that at least one of the former’s institutions in the Federalist Society was an indispensable prerequisite for the wins at hand — and the latter was similarly instrumental in the strategic orientation that set the institutions to their work. We should therefore think about things more expansively, not in the framework of right-populism versus right-institutionalism, but in the productive synthesis of the two. What we see in the wins of the past several days, or even the past several years, is actually more that synthesis at work than a victory of one over the other.

A reference to Boydian information-and-action theory is helpful here in framing the synthesis and how it actually works. I will reference concept more than discrete and named persons and entities here, for obvious reasons, but the reader will complete the picture to his own satisfaction.

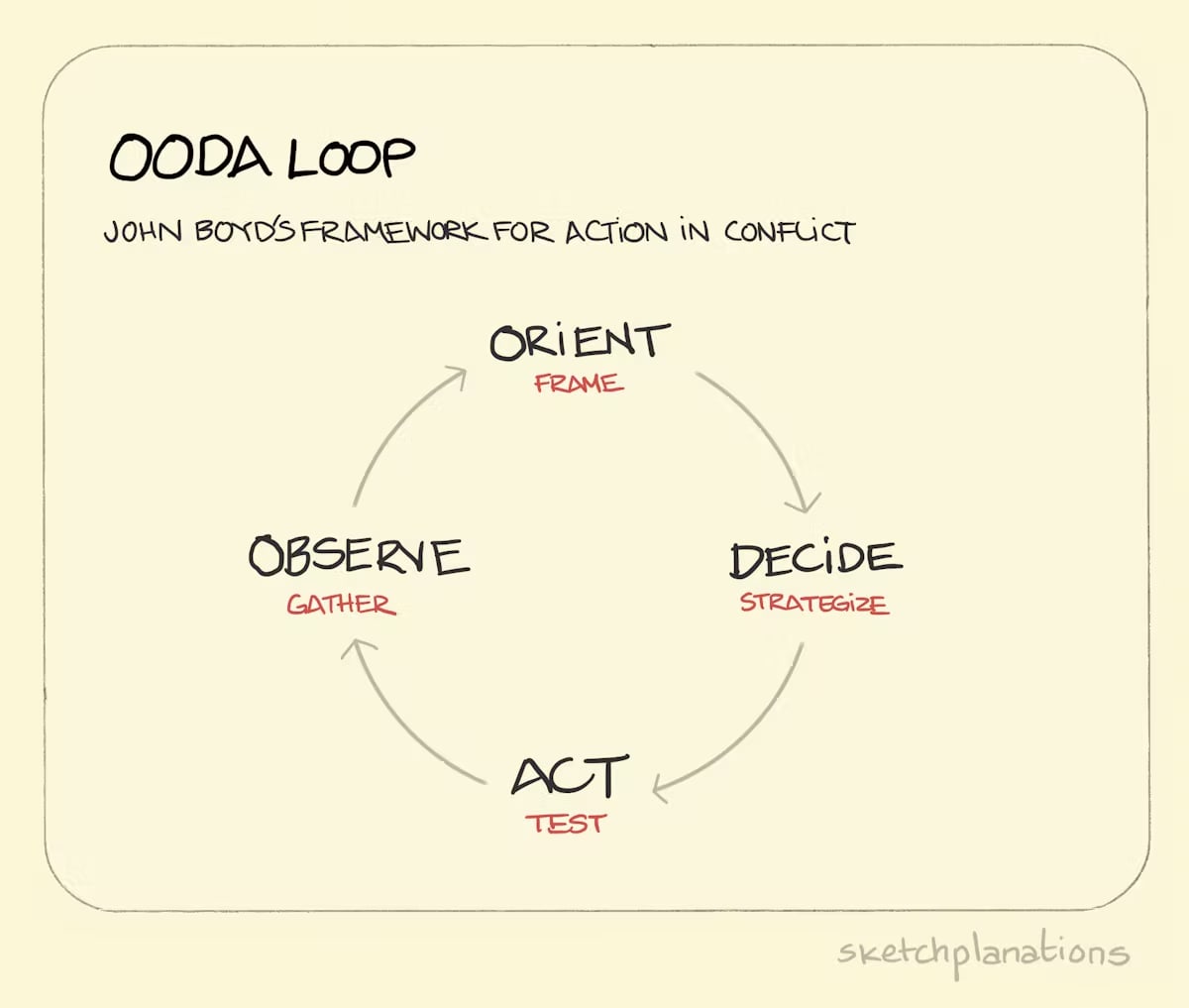

John Boyd’s OODA loop is a commonplace now, so much so that its analytic utility for prescription is significantly diminished: it’s the sort of product that declines in value with each new sale. Its value for analysis remains, however, and we will invoke a simplified model of it here. Setting aside Boyd’s full model — which is strewn with independent inputs and localized feedback loops — we can use the simplified big loop thus:

Observe — Information-gathering activity on a context, scenario, landscape, etc.

Orient — Placing oneself within the observed framework.

Decide — Discerning proper or advantageous action given the prior observation and orientation.

Act — Execution of the decision.

The final step, action, by its nature modifies the context and compels a return to the observation phase, thus the continuous loop.

The loop, properly understood, is not a singular process existing in isolation. There are many simultaneous contending loops, and each of them affects the others in some fashion. (In a meaningless item of trivia that Boyd would have appreciated, the only exceptions are those existing beyond the causal horizon of the universe.) There is a popular understanding of the OODA loop’s imperative as mandating speed — the faster loop in a competitive system “wins” — and it is rooted in Boyd’s own background in tactical aviation. But this, as Boyd himself noted, is not wholly accurate. Speed may be one imperative of the loop, and there are contexts in which it is the overriding or sole imperative. This is one of the things the observation and orientation phases are meant to discern. But there are other possible imperatives: control of operational tempo may be an end in itself, for example, in which case there may be an interest in compelling a slowness of operations.

One of the interesting things about the loop’s framework is that the observation and orientation phases imply an objective reality to which the agent within the loop is grasping. There is a truth, and efficacy of the subsequent decision and action phases rest heavily upon alignment with it. This is both nice for the vanishingly small cohort interested in philosophy, theology, and the theory of war; and also prospectively paralyzing for the decider who must judge how much information-gathering is enough. We can reference George McClellan from history here, who would have reconnoitered forever if allowed: but at some point one must plunge into the fray.

There are two major solutions to this problem. One is that a parsimonious theory of events, a heuristic, must be constructed, eliminating the need for a more-comprehensive informational phase. The other is that decision and action must be so outstandingly good, so evidently superior, as to negate any shortfalls from inferior observation and orientation. Neither of these answers is necessarily wrong, but they carry with them inherent risks. A parsimonious theory or heuristic shorthand can accrete error across time as the reality it is meant to describe moves beyond it. Decision and action predicated upon an incompleteness of information, known or unknown, can actually suffer from its own success by reason of that incompleteness. This is what gets you the Americans triumphant in Baghdad in April 2003, or the British triumphant in Charleston in May 1780, each headed for a major correction in time.

This brings us back to the populist and institutional rights now. The bifurcation is imperfect: there are plenty of populists in institutions, and there are major institutions that could be described as Conservative Inc. with populist leadership and direction. But this is supportive of the major point at hand, because in thinking of these two putatively opposed cohorts as actually constituting a productive synthesis, we ought to perceive them as engaged in a mutual correction of their respective Boydian loops. To return to the opening anecdote above, we can simplify the respective contributions of each cohort: the Conservative Inc. apparatus provided decision and action in its litigation, and the populist / NatCon apparatus provided observation and orientation to make it so.

To put it in concrete terms, you don’t overturn Dobbs and Chevron without first electing Donald Trump.

Illuminated here is the broader critique of the institutional right that has been gathering force across the past decade, which is that its observation and orientation have been inaccurate for some time. Its heuristic of understanding, which cohered across a twenty-year period from about 1964 to 1984, sufficed until it did not. When major elements of that heuristic were demonstrated as invalid — for example in national defense in the 2000s, and in trade in the 2010s — it failed to adapt internally, leading to the rise of an external force that has been integrating with it, and changing it, since. The efficacy of the apparatus was never in question: contrary to the oft-repeated criticism that conservatives have conserved nothing, let us defer to the wisdom of the late Stafford Beer in affirming that the purpose of a system is what it actually does. Because of the prior observation / orientation heuristic, so badly unaligned with reality as it was, the old order was never turned toward a conservation of anything — except to the extent it slowed down the left’s march. Conservatism Inc. didn’t require an overthrow, but a correction, in observation and orientation.

The agents of its correction also benefitted from what Conservatism Inc. or the institutional right did well, which was decide and act. I will betray my own policy biases here in the concrete examples given, nevertheless as a sympathetic observer who finds the National Conservatives and populists as excellent — and increasingly correct — aids in observation and orientation. It is, for example, totally true, as those cohorts note, that American national security and foreign policy is badly off course: an observation / orientation failure by the institutionalists. It does not follow from this that the solution is to, say, disband the North Atlantic Treaty Organization or delegitimize the postwar European superstructures: a decision / action failure. It is interesting to note that when in government, these corrections tend to become effectively mutual, with the NatCon / populist orientation and observation prevailing, and the institutional decision and action prevailing, each upon the basis of the other. To repeat myself at the outset, this is the fruitful synthesis.

We can put this a bit differently: the major achievement of the populist / NatCon cohort has been asserting dominance of strategy, with institutional perception and prudence shaping and directing operations and tactics. Each requires the other, and both are virtuous.

It is useful to think of the recent elections in both France and Britain in this framework. The superficial analysis is that each nation went in opposite directions: France veering right, Britain left. But thinking in the Boydian framework yields something different, which is a sameness between them. Both electorates rebelled against a regime that retained a badly inaccurate observation and orientation of itself toward reality — and in Britain’s case, one that furthermore showed itself incompetent to undertake the action phase of Boyd’s loop. The evident desired strategic reorientation is mostly the same in both countries — this assertion depends upon whether one accepts the proposition that Britain’s Tories lost rather than Labour positively winning, which I think is inarguable — and it is toward an emphatic defense and promotion of the interests of the existing citizenry, versus its imposed newcomers. Here we see a positive enthusiasm in both nations for proper alignment yielding action.

This is what the future of the right looks like, at least in the United States and most of the West that retains a grounding in something like a common liberal tradition. (This analysis probably does not apply to, say, Latin America, which has a very different context and inheritance.) The fruitful synthesis of the post-2015 NatCon / populist right and the institutionalist right of Conservative Inc. will continue to progress and deepen. I should be clear here that I do not mean the former will simply assume direction of the latter’s policies. (I definitely do not mean that the latter will largely thwart the former’s policy goals.) Policies are going to change, and already have. What I mean is that the right in the United States, and likely in much of Europe, is going to find itself — after an occasionally convulsive process that is probably already in its latter phases — more effective and more dynamic than it has been in over a generation, because its alignment with reality will conform it better to Boyd’s concept than any of its competitors. It is happening in plain sight.

The future of the right, in other words — and this is perhaps not easily discernible from the D.C. hothouse, but it is manifest elsewhere — is not a factional contest of either / or. It is both / and. And that’s why, in time’s fullness, it is going to win.